Context: Global efforts to combat climate change place the transport sector, a top-five global emitter, as a critical focus of decarbonization under the Paris Agreement. While rapid advances in battery technology, vehicle range, and charging infrastructure are accelerating the technical feasibility of electric vehicles (EVs), adoption patterns remain uneven across regions and demographics. This disparity underscores that consumer psychology, perceptions, and behavioral attitudes must complement technology and economics for success.

1. Climate Change and the Urgency of Decarbonization

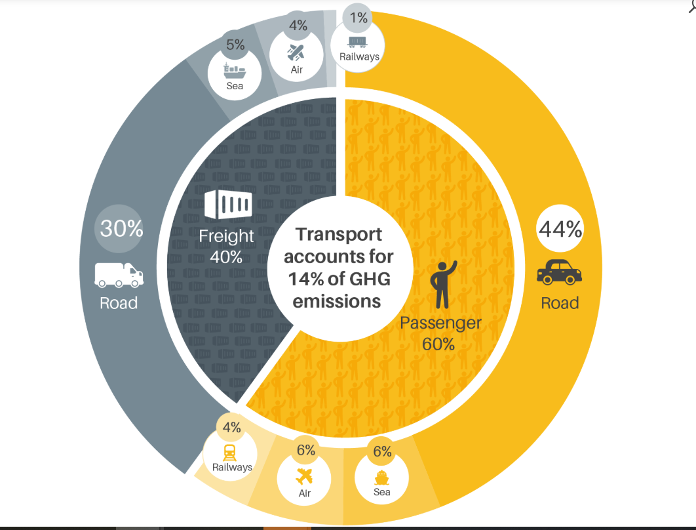

Climate change is among the most pressing global challenges of our time. The Paris Agreement calls for limiting the rise in average temperatures to well below 2 °c and ideally to 1.5 °c above pre-industrial levels [1]. The target makes decarbonization an absolute necessity, with the transport sector at the heart of this mission. In 2018, the sector was responsible for around 14% of global greenhouse gas emissions [2], and nearly 95% of its energy demand was still reliant on fossil fuels [3].

Source: https://tcc-gsr.com/global-overview/global-transport-and-climate-change/

Therefore, to truly decarbonize this sector, an accelerated transition is required not merely toward more efficient engines, but toward zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs), including battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and fuel-cell electric vehicles (FCEVs). Without such a transformation, the ambition of achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 will remain out of reach.

2. Technology and Economics: Progress So Far

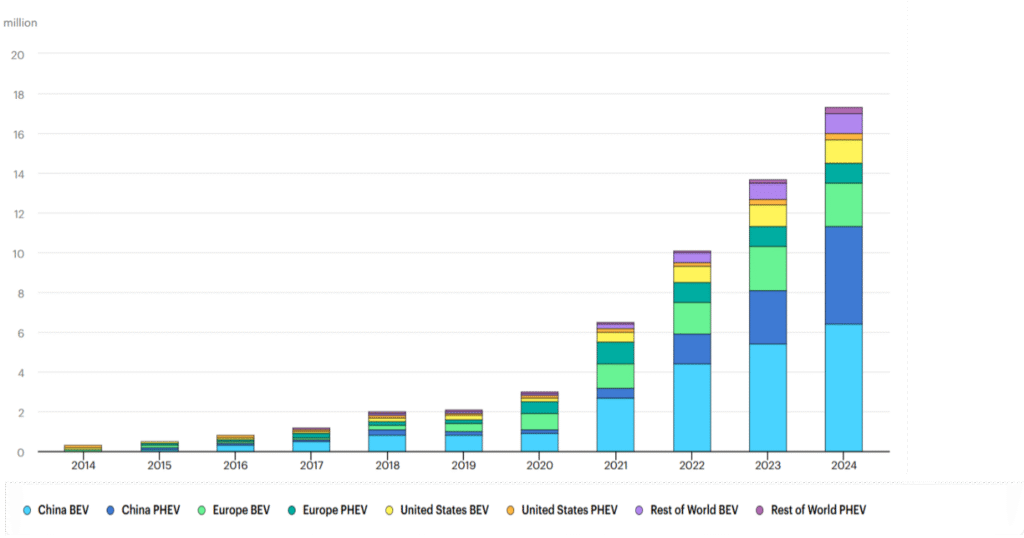

For years, the prevailing consensus was that EV adoption would remain constrained by high upfront purchase costs, insufficient charging infrastructure, and range anxiety [4]. These barriers are real but it would be misleading to suggest that progress has been negligible. Over the past decade, electric vehicles (EVs) have experienced an unprecedented surge in adoption.

Source: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/global-electric-car-sales-2014-2024

In 2024 alone, EV sales exceeded 17 million units worldwide, with a growth of more than 25% compared to 2023. By the end of the year, the global stock had expanded to 58 million vehicles. Battery packs declined by more than 25% with increased capacities, the driving range of many models exceeding 400km and over 1.3 million new public charging points were installed, more than double the network available just four years earlier [5].

3. The Persistent Gap in Adoption

These milestones highlight a pivotal reality: EVs are no longer confined to niche markets but are steadily becoming a central part of mobility systems. Despite the record growth, EVs still account for only 4% of the global passenger car fleet, with fossil fuel vehicles dominating the remaining 96% [5]. The gap is beyond technological advances and economic incentives alone; consumer behavior and psychology are also decisive.

4. Insights into Consumer Behavior

Recent studies emphasize that electric vehicle (EV) adoption cannot be explained by technology and cost curves alone; it is equally shaped by consumer attitudes, perceptions, and social dynamics. A review on the psychological, human, and socio-technical aspects of EV adoption highlights that attitudes, expectations, and self-efficacy – consumers’ perceived capability to switch to EVs and integrate them into their identity, must be leveraged to drive behavioral change [6].

A study used a moderated mediation framework [7] and found that perceived value strongly influenced purchase decisions, especially for higher-income buyers who could more easily act on the benefits they saw. Fascinatingly, the strongest driver wasn’t cost, it was sustainability perception, consumers wanted EVs to stand for something bigger than transportation: a personal commitment to greener living. Income made that link even stronger and environmental concerns give them further push.

Interestingly, social influence and peer pressure was weak, suggesting EVs are still regarded as an individual lifestyle choice rather than a collective trend.

Other studies reveal even more nuances. A Harvard study [8] analyzed over a million charging station reviews from EV drivers across North America, Europe, and Asia. Drivers today aren’t plagued by “range anxiety” but “charge anxiety”. The problem was caused by inconsistent pricing models across providers, poor transparency compared to gas stations, and regional disparities in infrastructure, which caused unpleasant surprises at charging points. Clearly indicating the need for trust, consistency, and transparency in user experiences and not just expanding charging networks.

Cultural and social contexts also add layers of complexity. In Spain, EV adoption isn’t just linked to education and income but most particularly status and reputation, when EVs are more expensive, they carry the prestige as luxury goods which becomes their motivator [9]. In Taiwan, the dynamics is different: peer influence and media coverage are the strongest drivers, reinforced by attitudes, perceived control, and practical enablers such as charging infrastructure and government incentives [10]. In Portugal, knowledge and peer influence are less important instead adoption is driven by attitudes like “EVs are simple and practical” and norms like “it’s my duty to reduce pollution.” Generational differences exist, but what really matters is the moral sense of responsibility [11].

China had a fascinating facet. An innovative study used an agent-based real-time game model to simulate how EV adoption spreads where, “agents” representing consumers influence one another through interaction and mimicking real-world social networks. The results were striking indicating that adoption spreads faster when interactions are frequent and further amplified by social media platforms such as WeChat, Douyin, and Bilibili.

The model demonstrated that “simply making internal combustion vehicles (ICEs) less attractive is not enough because buyers are loyal to what’s familiar” [15]. To enable EV market penetration their unique advantages must be emphasized and innovators must lead to accelerate cultural acceptance.

The case of the UK reinforces the importance of consumer identity. Using a detailed stated-preference dataset and advanced econometric modeling, researchers found that the typical early adopters are most likely younger, highly educated, often students, married, and based in southern regions. What mattered most in their consideration? Purchase cost, performance, range, and environmental friendliness.

Education had the strongest and most significant impact, particularly students indicating high openness to clean technology. Surprisingly, Income was statistically weak. This likely reflects both the steady drop in EV prices and the growing public expectation that costs will continue to fall in the near future [13].

Taken together, these studies reveal a crucial lesson that consumer behavior greatly influences adoption.

Conclusion & Reflection

This is not to downplay the technological dimension. Expanding renewable grids, driving down vehicle costs, and scaling up charging infrastructure are all essential but adoption is not purely technical, it is equally about consumer perception, values, and behavior. What’s especially fascinating is how these motivations differ from country to country:

- In Spain, EVs are about status.

- In India, about value and sustainability.

- In Taiwan, about social influence.

- In Portugal, about moral duty.

- In China, about interactions and media.

- In the UK, about education and openness.

These differences make one thing clear: there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Even the most advanced technology designs won’t guarantee adoption everywhere, it’s highly dependent on the consumer. Technology opens the door, but consumer psychology decides whether people walk through it. How people think, feel, and identify with EVs must be addressed alongside technical innovation for successful decarbonization.

References

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), “The Paris Agreement,” 2016. [Online]. Available: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement#:~:text=The%20Paris%20Agreement%20is%20a%20legally%20binding,entered%20into%20force%20on%204%20November%202016

- Transport and Climate Change Global Status Report, “Global Transport and Climate Change,” 2021. [Online]. Available: https://tcc-gsr.com/global-overview/global-transport-and-climate-change/

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), “Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions Data,” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/global-greenhouse-gas-overview

- MIT Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research (CEEPR), “Challenges to Expanding EV Adoption and Policy Responses,” 2022. [Online]. Available: https://ceepr.mit.edu/challenges-to-expanding-ev-adoption-and-policy-responses/

- IEA (2025), Global EV Outlook 2025, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2025, Licence: CC BY 4.0

- G. Rainieri, C. Buizza, and A. Ghilardi, “The psychological, human factors and socio-technical contribution: A systematic review towards range anxiety of battery electric vehicles’ drivers,” Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, vol. 99, pp. 52–70, 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.trf.2023.10.001.

- S. Y. Kottala, S. Chanagala, C. Balaji, V. V. N. Reddy, and G. N. P. V. Babu, “Exploring electric vehicle consumer behavior: impact of digital innovation, environmental concern, perceived value, and social influence on purchase intentions,” Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, vol. 7, Sep. 2025, doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1655074.

- Harvard Business School, “The State of EV Charging in America,” Institute for the Study of Business in Global Society (BiGS), 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.hbs.edu/bigs/the-state-of-ev-charging-in-america

- K. M. Buhmann and J. R. Criado, “Consumers’ preferences for electric vehicles: The role of status and reputation,” Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, vol. 114, p. 103530, 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.trd.2022.103530.

- H. Zhao, F. Furuoka, R. A. Rasiah, and E. Shen, “Consumers’ purchase intention toward electric vehicles from the perspective of perceived green value: An empirical survey from China,” World Electric Vehicle Journal, vol. 15, no. 6, p. 267, 2024, doi: 10.3390/wevj15060267.

- J. Campino, F. P. Mendes, and Á. Rosa, “The race of ecological vehicles: consumer behavior and generation impact in the Portuguese market,” SN Business & Economics, vol. 3, p. 148, 2023, doi: 10.1007/s43546-023-00524-2.

- M. Chen, R. X. J. Liu, and J. Hao, “An Agent-Based Real-Time Game Model for Forecasting the Market Penetration of Vehicles in China,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 24631–24643, 2024, doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3365488.

- F. Mandys, “Electric vehicles and consumer choices,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 142, p. 110874, 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2021.110874.

- K. M. Buhmann, J. Rialp-Criado, and A. Rialp-Criado, “Predicting consumer intention to adopt battery electric vehicles: Extending the theory of planned behavior,” Sustainability, vol. 16, no. 3, p. 1284, 2024, doi: 10.3390/su16031284.